Back in January I discussed the Golden Rod Cake and the pan used to bake it. We did find several recipes, but were left wondering about what the cake was supposed to look like, and about the origin of the name. I have since found a tiny bit more information about this elusive cake.

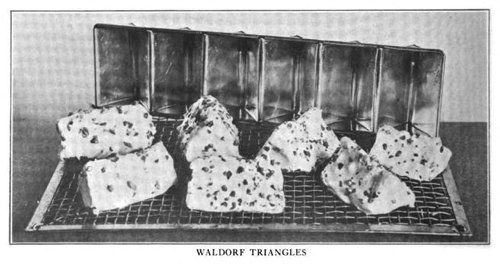

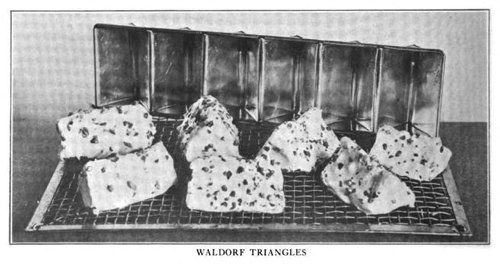

This photo of Waldorf Triangles and their triangular pan is from American Cookery, April, 1921, p. 680. It accompanies this recipe:

Waldorf Triangles

Beat the yolks of six eggs very light; gradually beat into these half a cup of granulated sugar, then two tablespoonfuls of orange juice. Lastly, add half a cup of sifted flour, sifted again with a level teaspoonful of baking powder and a few grains of salt. Put the mixture into Waldorf Triangle pans and bake in a moderate oven. As soon as the cakes are turned from the pan cover the sides with boiled frosting and sprinkle with fine-chopped pistachio nuts.

This should sound familiar, because it is nearly word-for-word the same as the recipe “Goldenrod Cake for Charlotte Russe Moulds and Waldorf Triangles” that the Boston Cooking School published in an earlier version of their magazine in 1904 and 1905, and that I included in my earlier post. One of the 1904-1905 recipes includes the boiled frosting and pistachio nuts, but the other does not. The older recipes also do not refer to the pans by name as “Waldorf Triangle pans.”

The title of the early Boston Cooking School recipes seems to be pretty clear that this is a recipe for Goldenrod Cake that can be used to make Waldorf Triangles. Other early recipes, however, do not mention the pistachios, and frequently mention orange icing.

The Rocky Mountain Cook Book: for High Altitude Cooking (1918 edition of a 1903 cookbook) includes a nearly identical one to the BCS recipe:

Golden Rod Cake.

Beat the yolks of six eggs till light; gradually beat into these one-half cup of sugar, then two tablespoonfuls of orange juice and one-half cup of sifted flour, sifted again with a level teaspoonful of baking powder and one-fourth teaspoonful of salt; bake in small cakes and cover with orange icing.

This is the same as the BCS “Goldenrod Cake for Charlotte Russe Moulds and Waldorf Triangles” and the later American Cookery “Waldorf Triangles” recipe, with one exception — the end. No mention of boiled icing sprinkled with pistachios, just orange icing. Could the pistachios be the defining characteristic of Waldorf Triangles? One of the BCS recipes doesn’t mention them either. Perhaps the cakes are Golden Rod Cakes if they have orange icing (or none?) and Waldorf Triangles if they have pistachios.

(Incidentally, the author of The Rocky Mountain Cook Book, Caroline Trask Norton, was a graduate of the Boston School of Domestic Science, so perhaps it should not be surprising that the recipe is similar to the BCS version.)

The recipe in 365 Orange Recipes: An Orange Recipe for Every Day in the Year is called “Goldenrod Cake” and says “Bake in goldenrod pans and when cold ice with the following Icing,” going on to describe an icing made from orange rind, egg, sugar, water, orange and lemon juice, and “sugar to make as thick as fondant.” The icing is then colored orange.

There are a couple more references to these recipes that could add clarity to the situation, or perhaps just muddy it further.

The Boston Cooking-School Magazine October 1905, p.174, has this recipe:

Waldorf Triangles

Prepare the goldenrod cake mixture given on page 91 of August-September, 1904, issue of the magazine. Bake this in goldenrod pans (it will take two pans, each holding six triangles). When the cakes are baked, cover the sides with confectioner’s frosting or with fondant, then sprinkle with blanched pistachio nuts, chopped fine.

The implication here is that Golden Rod cakes become Waldorf Triangles by the addition of frosting and chopped pistachios.

Then there is What To Cook and How To Cook It 1899, by Mrs. W. A. Johnson of Paris, Kentucky. In the appendix, on page 282-283, we find:

Waldorf Triangles or Golden Rod Cake.

One-fourth cup of butter, one cup of confectioner’s sugar, one-half cup of milk, two cups of flour, one level teaspoon of baking powder, two eggs, the grated rind and juice of one orange. Bake in orange quarter baking pans. Put a small quantity in each section and spread evenly. Spread orange icing over each triangle, made by mixing confectioner’s sugar with enough orange

juice to spread evenly.

Well, there’s the orange icing. No pistachios this time. And the title calls these either Waldorf Triangles or Golden Rod Cake, implying that they are alternate names for the same thing.

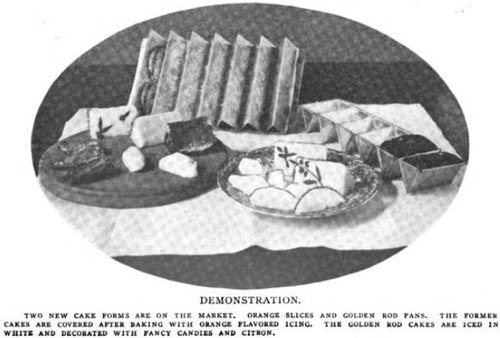

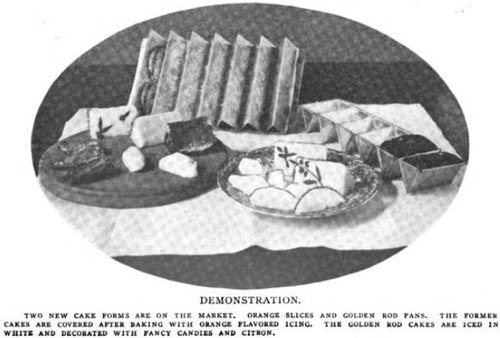

And then I found this photograph in the 1906 Table Talk Illustrated Cook Book:

The text reads: “Two new cake forms are on the market. Orange slices and Golden Rod pans. The former cakes are covered after baking with orange flavored icing. The Golden Rod cakes are iced in white and decorated with fancy candies and citron.” Here the Golden Rod cakes aren’t the orange ones, but they don’t have pistachios, either. No reference is made to Waldorf Triangles.

(I could go on. There are the German-American versions from Praktischer Ratgeber für Conditoren, Cakebäcker und Brotbäcker und Candy-Macher/Practical Manual for Confectioners, Pastrycooks and Bakers and Candy Makers, 1912, that parallel the 1890s versions I found in my previous post, and one of which specifically calls for “three-cornered, long pans” [“long” is left out of the English translation on that page, but it’s there in the German].)

My thought, after all of this, is that Golden Rod/Goldenrod Cakes are probably the basic triangular cakes, usually iced with orange icing (and perhaps frequently conflated with the Orange Slice cakes which had a slightly different pan, but could also be made in the Golden Rod pan), and that Waldorf Triangles were a variation (presumably originating at the Waldorf Hotel?) that had pistachios and were not orange. This is really only speculation, subject to change as I find more information. I look forward to finding more versions of these recipes and researching this further, and to possibly trying the recipe one of these days.

I’m also looking forward to finding one of the darn pans! No luck so far.