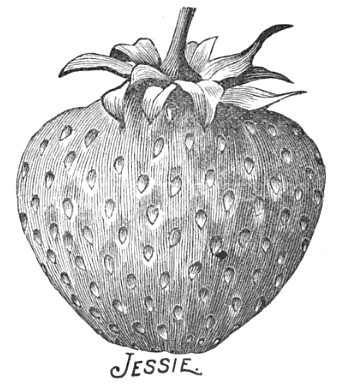

Strawberry festival season

It’s June, which means that it’s strawberry season! (Well, usually it is. This year, the Northwest weather has been unusually cold, and so I bet the strawberries are running late.) If it’s strawberry season, it’s time for a strawberry festival, with some strawberry recipes and menu ideas!

110 years ago in June 1901, Good Housekeeping published “XXth Century Festivals: The Strawberry Festival,” suggesting that festivals should be held on a moonlit evening and furnished with tables with fine white linen tablecloths and fern decorations. The dishes should be strawberry red, green, and white.

The suggested centerpiece (which “should have a place of honor”) sounds quite lovely for a summer twilight party:

“In a conspicuous place set a table holding a glass bowl of strawberry frappe or lemonade, to be served in small glass cups. A block of ice hollowed out, with a lighted pink candle inside, may be put in the center of the bowl, and the frappe heaped around the ice, insuring coolness. Decorate the table with strawberry vines or ferns, and have two white-robed maidens to serve the frappe.”

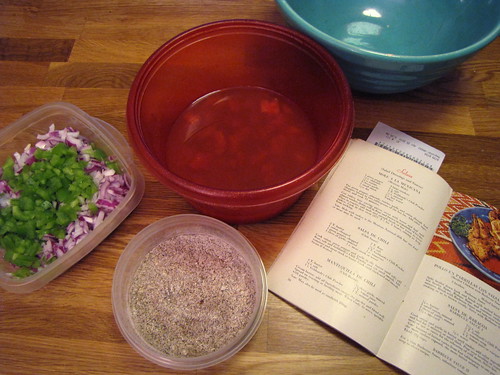

Here is the recipe given a few pages later for the frappe:

Strawberry Frappe

- 4 cups water

- 2 cups sugar

- Juice of 6 lemons

- 4 cups mashed fresh strawberries

The following recipe makes a very delicate frappe. Boil for fifteen minutes four cups of water and two cups of sugar, add to it the juice of six lemons and four cups of mashed fresh strawberries or one quart of the canned fruit.

Allow it to cool, strain and add one quart of ice water.

Freeze to a mush, using equal parts of ice and salt.

If you use canned fruit which is very sweet the frappe may not require so much sugar.

Good Housekeeping‘s suggested menu for the event might be slightly different from a modern menu, but not terribly so:

STRAWBERRY FESTIVAL MENU

Cold ham / Cold tongue / Rolls

Saratoga potatoes / Tomato salad / Crackers

Pickles / Radishes / Pimolas

Individual sweet shortcakes / Strawberries and cream

Strawberry ice cream / Strawberry eclairs

Sponge cake / Angel cake / Small cakes

Coffee / Chocolate

The magazine also provided some recipes for cakes and preserves to sell at the festival. Here is one example:

Strawberry Eclairs

- 1 cup boiling water

- 1/4 cup butter

- A speck salt

- 1 cup flour

- 4 eggs

- sweetened strawberries or jam

- boiled icing colored with strawberry juice

Boil together in a saucepan one cupful of boiling water, one-fourth cupful of butter, and a speck of salt.

As it begins to boil stir in one cupful of sifted flour.

Stir constantly until the mixture leaves the sides of the pan and cleaves together in a ball.

When partly cool add four eggs, beating them in one at a time.

Drop carefully in long narrow strips, some distance apart, on buttered tins, and bake in a moderate oven until well risen---about thirty minutes.

Leave the oven door open a few minutes before removing the eclairs, to prevent their falling.

When they are cool split one side, fill with sweetened strawberries or jam.

Spread with boiled icing colored with strawberry juice.

I plan to try this one and will report back.

(Editorial note 1: Pimolas appear to be what we’d probably call pimientos today — olives stuffed with sweet peppers. Perhaps the word is a portmanteau of “pimiento-olives”? Many menus of that period list them as “pim-olas.”)

(Editorial note 2: The formatting of the recipes is intended to be compatible with Google’s new Recipe View system. Though the formatting is slightly different than the 1901 original, the wording of the recipe instructions is unchanged.)