Browsing through Google Books (something I spend far too much time doing), I stumbled on an interesting article from a 1914 issue of American Cookery. At the time, World War I had newly broken out in Europe, but the United States remained officially neutral.

In this article, an American family declares war on expensive imported foods and converts the previous year’s Christmas menu to an American-grown feast for 1914. Consistent with the nation’s stand of neutrality, all traces of foreign content are removed, even the English plum pudding and the French word “menu.” But even in 1914, Americans couldn’t do without their coffee.

Censoring the Christmas Dinner

By Stella Burke May, American Cookery, December 1914

A state of war existed in the hitherto peaceful household of the American John Smith, for Mrs. John Smith, generalissimo of the kitchen, had declared war on foreign food products.

Among the causes which led to this declaration were, first; that the Smith household was being constantly menaced by the air fleet of Imported Products, which had dropped a High-Cost-Of-Living bomb on its commissary department, and second; that foreign invasion, during the past twelve months, had well-nigh wrecked the John Smith treasury.

In proof of this latter accusation, Mrs. Smith produced her Christmas menu from the previous year, which showed the foreign element in strong supremacy.

Feeling the need of support from a strong ally, she called her husband from his evening newspaper, and showed him the line-up of his last year’s Yuletide dinner.

“Shades of the Father of His Country,” exclaimed John as he glanced over the card. “No wonder they had war in Europe!”

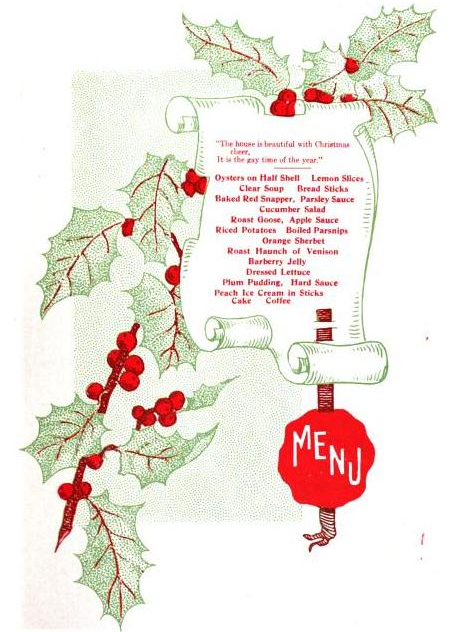

This is what he read:

Christmas Dinner, 1913

Anchovy Canapés

Mushroom Consommé

Salted Wafers Celery Spanish Olives

Broiled Smelts Maitre d’hôtel butter

Roast Turkey Plain Dressing Duchesse Potatoes

Buttered Brussels Sprouts

French Peas Creamed Onions Cranberry Frappé

Chinese Celery Prune, Apple-and-Nut Salad

Neufchatel Cheese

English Plum Pudding Hard Sauce

Mandarin Oranges English Walnuts Malaga Grapes

Café Demi-Tasse

So, even as the European press censor, pencil in hand, goes over his war dispatches, deleting a word here, a phrase there, lest his own particular country appear at a disadvantage or the enemy profit by the context, did Mrs. John Smith go over her Christmas bill of fare, eliding every foreign combination and condiment, and steering clear of the high C’s of yester-year such as “canapés, consommés and cafés,” this American censor effaced all evidence of foreign domination, and launched her transport upon neutral waters from cocktail to coffee.

With patriotism coupled with ingenuity, she set herself to the task of preparing a dinner that might stand uncovered as the flag goes by.

“I will avoid even the appearance of partizanship (sic),” she told herself, “and not even call this a menu. It shall be a bill-of-fare this year.”

“And there must be no foreign flavor, no paprika, no French or Italian olive oil in the salad, no imported wines or brandies.”

They both agreed that a canapé was decidedly contraband, and while it might serve if disguised under the title of “appetizer,” felt that Baltimore oysters served on their native shell, with Iowa horseradish, Oklahoma catsup, and thin slices of California lemon would be in strict neutrality.

The consommé must become a soup; not even a bouillon, but a plain vegetable soup, and asparagus seemed to meet all the maritime laws.

If the market afforded fresh radishes, they would be added to the soup course, but in no event would Spanish olives pass muster. In fact all “hors d’oeuvres” were now “hors de combat.”

The fish course was abandoned as an extravagance, since oysters were to open the meal, so the maitre d’hôtel butter was thus disposed of.

“How would it be to buy the turkey on the ‘hoof’ this year?” queried her husband. “I will kill and dry-pick it and you can hang it in the refrigerator for a couple of days before Christmas.”

“Turkey! Turkey!” exclaimed his wife in supreme astonishment. “Why, John Smith, we’re not going to have a fowl with a foreign name like that. We’re to have roast goose, with chestnut stuffing.”

For the main course, then, it would be roast goose, with chestnut stuffing and potatoes.

“Remember,” cautioned John, “there will be no vegetable with a foreign name like Irish potatoes.” So avoiding the belligerent waters in which sailed “‘potatoes a la Hollandaise,’ French fried, German fried, au gratin, O’Brien, Hongroise” she landed at sweet potatoes, Southern style, and added this to her card.

Brussels sprouts came under the same indictment. “I always have thought Brussels sprouts are just sort of ‘babes-in-the-wood’ cabbages that lost their way, so I think we will just have creamed cabbage and be done with it.”

“Onions ought to pass without an investigation,” John said, as he watched her writing “baked onions,” “but be sure they’re not Bermudas and have no foreign flavor.”

Next, cranberry frappé was shorn of its alien looks and appeared in homespun as “cranberry jelly moulded,” and the understanding was that they were to be Wisconsin grown.

Small light rolls made with Minneapolis flour would be served with the meat course.

The salad course was quickly disposed of. Following the dinner of the previous year, she chose a salad of apples, celery-and-walnuts in heart lettuce cups. She would insist on New York Jonathan apples, Michigan celery, Illinois walnuts and Florida lettuce, served with a cream dressing. In place of the Neufchatel cheese, she would serve cottage cheese spread between thin slices of brown bread, along with the salad. The “yellow peril” celery was, of course, taboo.

“I don’t see why they always have English plum pudding, when New England minced pie contains all the ‘stuff that dreams are made of,'” said John, and, his Commissary General agreeing with him, resolved to have New England minced pie with frozen pudding.

For nuts she selected Georgia paper-shell pecans. These, with Florida tangerine oranges and California raisins would seem sufficiently “censored.”

And, lastly, of course, coffee in half cups, with Louisiana cut-loaf sugar and home-grown cream. She realized she must call upon her neighbors in South America for the coffee, but they both agreed that Brazil coffee in a Connecticut percolator should pass the most captious critic.

Assembling her national dinner, this was what she produced:

Christmas Dinner, 1914.

American Plan.

Baltimore Oysters on Half Shell

Served with horseradish, catsup and thin sliced lemon

Asparagus Soup

Salted Wafers Fresh Radishes

Roast Goose

Chestnut Stuffing

Alabama Sweet Potatoes, Southern Style

Baked Onions Creamed Cabbage

Cranberry Jelly in Moulds

Small Light Rolls

Apple-Celery-Walnut Salad in Heart Lettuce Cups

Brown Bread-and-Cottage Cheese Sandwiches

New England Minced Pie

Frozen Pudding

Florida Tangerines Georgia Paper Shelled Pecans California Raisins

Half Cups of Coffee

Louisiana Sugar Cream

So, stripped of her foreign garments, and clothed in a brand new gown with a fine domestic finish, we behold the American Christmas dinner for the Americans at home, and while we greet our guests, the American John Smith will insert a new needle and start “The Star Spangled Banner.”

(Want to see a few more Christmas menus? Stay tuned. I’ll post some more later today.)