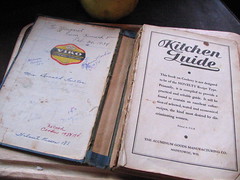

When flipping through Mexican Cookery for American Homes (1936) last week looking for a recipe to try that we would also be willing to eat for dinner, I saw a recipe for Enchiladas, Mexican Style. “Sounds good,” said Jason. “Make that.”

Here is the recipe as it is in the book:

ENCHILADAS, Mexican Style

| 18 tortillas |

1 c. grated cheese |

| 1/2 c. fat |

1 c. chopped onion |

| Chili Sauce (recipe p. 36) |

6 eggs, fried |

| Salt to taste |

If tortillas are cold, heat in hot fat until they are softened and are golden brown in color. In a saucepan, heat the chili sauce. Dip the hot tortillas in the hot chili sauce and remove to plate; sprinkle each with cheese and finely chopped onion. Serve in stacks of three, topped with a fried egg and two or three tablespoons of Chili Sauce.

Wait, what? Stacked, flat enchiladas? I had never heard of such a thing. When I’ve made enchiladas before, they have always been filled, rolled, and baked in chili sauce. (Yum, I might add.) This odd “flat enchilada” piqued my interest.

As it turns out, is not exactly a resurrected recipe—flat enchiladas are still commonly made in New Mexico, Sonora, and a few other places. In New Mexico, it’s considered a local specialty. Up here in the Seattle area, though, enchiladas are usually rolled, at least in the restaurants I’ve visited.

Barry Popik’s website, The Big Apple, discusses the history of the flat or stacked enchilada, giving several recipes including a recent one by Bobby Flay that is fairly similar to our 1936 recipe, and one dating back to 1950.

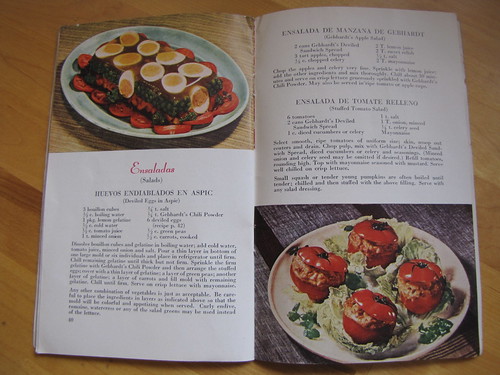

The flat enchilada can be found earlier than 1950, however. Here it is in “A New Mexico Supper,” American Cookery, October, 1921:

“Las Enchiladas, for instance, are unlike anything else under the sun. You may follow, if you like, the fascinating process of concoction of this piece de resistance of your meal. The senora is frying tortillas, the corn pancake which is the foundation of the enchilada.

“From a snowy mass of corn meal dough she pinches a ball which she spins and pats between her plump hands into a thin wafer about six inches in diameter. She browns this on top of the stove, rotating and turning it with her moistened palm. When three tortillas have been beautifully browned they are next dropped into a kettle of boiling fat where they bubble and turn until the real building process begins.

“First a tortilla in the center of a plate. Then a flood of rich red chile sauce from a near-by kettle, a layer of grated cheese, another tortilla, more chile and more cheese sprinkled between in layer-cake fashion, and the whole topped with a high crown of chopped onions in which nestles an egg, which has been broken for a minute into the hot lard. An artistic and cooling garnish of lettuce—and behold an enchilada!”

The flat “Mexican Style” enchilada recipe in Mexican Cookery for American Homes is on the same page as a recipe labeled “American Style.” The “American” version is the rolled style: tortillas stuffed with hot chili from a can and then covered with chili as well, then sprinkled with grated cheese and placed in the oven just long enough to melt the cheese.

The “Mexican Style” sounds much more appealing, so I went with that. The first step was to turn to the Chili Sauce recipe on page 36.

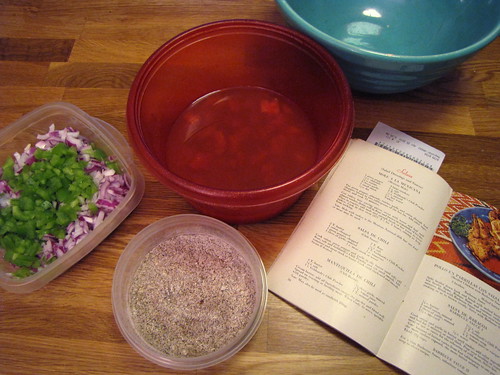

SALSA DE CHILI

(Chili Sauce)

| 2 T. butter |

2 T. flour |

| 1 onion, chopped |

1/2 t. salt |

| 1 green pepper, chopped |

1 T. Gebhardt’s Chili Powder |

| 1 clove of garlic, minced |

1 c. tomatoes |

| 1 c. meat stock or water |

Cook onion, green pepper and garlic in the butter until soft; add flour, salt and Gebhardt’s Chili Powder and stir until smooth. Add tomatoes and meat stock or water. Cook until thickened and smooth. Strain if desired.

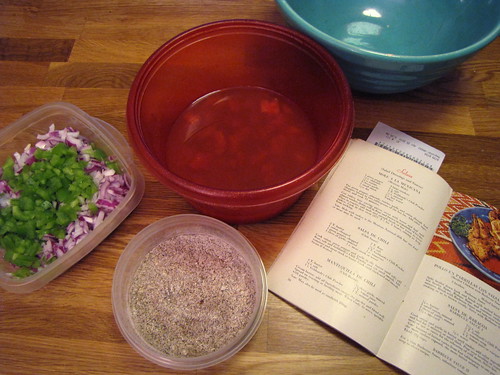

This is reasonably straightforward. The only changes I made to the recipe were using chili powder from Penzeys (their Medium Hot) instead of Gebhardt’s, and using vegetable stock instead of beef stock or water. I made the full recipe.

The chili sauce ready to go, it was time to make the enchiladas. I was only making one stack because Jason is currently not eating tortillas — he was going to use the chili sauce to make himself some huevos rancheros instead. The original recipe serves six, so I reduced the quantities as appropriate.

I heated up olive oil in a pan, and when it was hot, dipped each tortilla in the oil for about 5 seconds on each side, then dipped it in the sauce, then laid it out on the plate. The one problem I tended to have here was that I couldn’t stack neatly, since the tortillas kept wanting to fold in on themselves while I was trying to get them on the plate.

Neatly or not, I got each tortilla, now coated in saucy goodness, onto the plate, where Jason sprinkled cheese and onions on top of each layer.

I quickly fried an egg sunny-side up, and placed it on top of the stack, then sprinkled on some more cheese, onions, and a few spoonfuls of chili sauce, and a dab of sour cream. (Unfortunately, I don’t have a good photo of the finished eggy version.)

Verdict

This was excellent. I don’t think it is necessarily the healthiest thing I’ve ever cooked, what with the quick-fried tortillas and the egg and the cheese, but darned if it wasn’t one of the tastiest. I would cook and eat this again any time.

The chili sauce had a lot to do with the success of this recipe. I did let it thicken and reduce just a bit more than I should have, I think, but it was delicious. I chose not to strain it, so it was a bit chunky, but that wasn’t a problem at all. It wasn’t outrageously hot chili sauce, but it wasn’t exactly tame, either — you would take a taste and think “this isn’t hot at all, just flavorful,” and then a minute later the burn would hit you. And it was a good burn, not the kind of macho “more pain than flavor” burn you get from a lot of spicy foods these days. Of course, it might just be that the chili powder we used is really tasty.

We both felt that the sauce needed a bit of salt, but that wasn’t a big deal. Some of the information I found online about Gebhardt’s chili powder indicated that it might be as much as 40% salt, which would explain why our version that didn’t use Gebhardt’s needed some salt — the Penzeys powder we used contains only Ancho chili pepper, red pepper, cumin, garlic and oregano, but not any salt.

I can’t speak for authenticity or whether this really is “Mexican Style.” What I do know is that it’s pretty good, and I think I’ll introduce it to a few Seattle friends who may never have enjoyed a stacked enchilada before.

We had some leftover chili sauce and onions, and used that to resurrect another recipe on the next day. Stay tuned for a post about that one.